For many reasons, management of annual bluegrass weevils (ABW) presents incredible challenges to golf course superintendents in New York State. These reasons include:

For many reasons, management of annual bluegrass weevils (ABW) presents incredible challenges to golf course superintendents in New York State. These reasons include:

1) The small size (about 1/8 inch in length) and cryptic nature of ABW adults make monitoring difficult.

2) As the life stages progress and ABW transitions through the egg and larval stages, observing ABW becomes increasingly difficult because most stages occur within the turfgrass stem. Complicating things further, as larvae mature they emerge from the turf crown into the surrounding soil and proceed to feed on the crown and roots of the plant. Following the last larval development stage, larvae pupate below ground and the next adult generation emerges. This generation of ABW is more widely distributed on the golf course, and thus more difficult to find and diagnose than the previous generation.

3) ABW development is highly asynchronous, meaning that the life stages of different individuals overlap, resulting in the presence of more than one life stage at a single time.

Collectively, these factors make ABW a difficult insect to monitor and manage in an economically and environmentally sustainable way. However, by using proper scouting methods along with a well-informed decision-making process, the effectiveness and efficiency of ABW management can be improved at your facility. Traditionally, ABW management has focused primarily on scouting for and treating adults. However, to enhance control and to manage insecticide resistance in ABW, managers are encouraged to broaden their monitoring and management efforts to include ABW larvae in addition to adults.

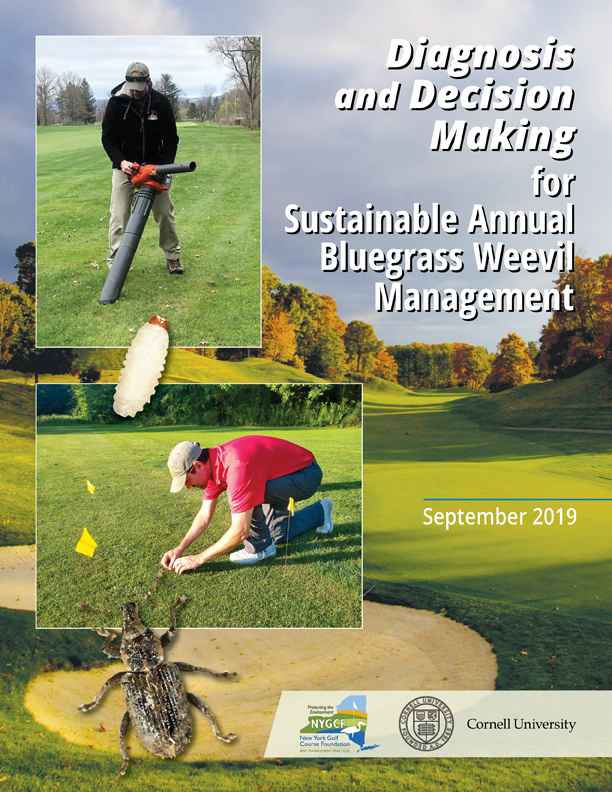

The new NYS BMP and Cornell University joint publication Diagnosis and Decision Making for Sustainable Annual Bluegrass Weevil Management provides the information superintendents need to establish a successful ABW monitoring and management program for both adult and larvae ABW.

Related content on the NYS BMP blog:

- Case Study on IPM Methods to Control ABW at Bethpage Black Course

- Detailed instructions on two different designs for easily creating a vacuum basket for monitoring ABW.

Our stand alone publication, Best Management Practices for Pollinators on New York State Golf Courses, has been revised and republished, now available for on-line reading as a flip book:

Our stand alone publication, Best Management Practices for Pollinators on New York State Golf Courses, has been revised and republished, now available for on-line reading as a flip book:  Pest management is a critical component of maintaining a playable and functional golf course. A fully implemented best management practices program demands the highest level of progressive

Pest management is a critical component of maintaining a playable and functional golf course. A fully implemented best management practices program demands the highest level of progressive